The secret to writing persuasive speeches

What is the purpose of a speech?

We can get really specific about this. Some speeches are about selling products or convincing investors to take a plunge. Others are about showing our love, replying to a critic, or launching a campaign.

Let’s zoom out a little. Most speeches, ultimately, are intended to persuade. They are about a speaker convincing an audience – which range from anywhere from captivated to hostile – about the merits of their argument. Vote for me. Invest in my company. Eat at my restaurant. Et cetera.

Even this broad categorisation doesn’t capture every type of speech. I wouldn’t consider a wedding speech, for example, to be an act of persuasion, for the reason that (at least at the average wedding) the audience is already persuaded about the love the beautiful couple has for each other. The average wedding speech is informational – it tells you, the audience member, something about the bride or groom that they didn’t already know (such as the time they got embarrassingly intoxicated and… yeah).

But, generally speaking, most speeches are acts of persuasion. This is especially true if you’re a leader – be it in politics, business, the not-for-profit sector, or wherever you ply your trade.

As a leader, your speeches will need to motivate. To inspire. To persuade. In fact, they will often need to go further still: your speeches will need to move people to action.

Today, I want to introduce a speechwriting technique that has persuasion right at its heart. It is an approach which, since first being formalised, has become a staple of marketing and advertising. But remarkably few people know its name, its origins, or even the steps involved.

This is the story of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

Who was Monroe?

To begin, let’s get a sense of the man behind the message.

Monroe is Alan Houston Monroe, an American psychologist, author, and pioneer in the field of communication. He was born in Illinois in 1903 and enrolled in Northwestern University at the age of 19. After graduating with a Bachelor of Science in 1924, he was hired by Purdue University as an instructor in English. Soon, Monroe was asked to create a course to address the burgeoning field of communications and public speaking. The course he created, Communications 114 (COM114), remains a mandatory course for several degree programs at Purdue University.

Alan Houston Monroe

By 1928, Monroe had been promoted to the position of Assistant Professor of Public Speaking and became the head of the speech section of the English Department. He was clearly on an upward trend and his contributions to this emerging discipline were being noticed. After finding further success in the 1930s, including obtaining his PhD from Northwestern in 1937, Monroe was promoted to Chairman of the Section of Speech in the Department of English and Speech in the 1940/41 academic year.

Following more years of faithful service, Monroe resigned as the head of the Speech program in 1963. That same year, no doubt with Monroe’s input, Purdue University established a Department of Audiology and Speech Science (today called the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences).

What did Monroe say?

Dr. Monroe passed away in 1975, but not before publishing his thoughts on the science of communication in a book called The Principles of Speech Communication.

This book is where Monroe formalised his sequence. So now that we’ve arrived at that part of the story, let’s get into it. What is Monroe’s Motivated Sequence and how can it help us write persuasive speeches?

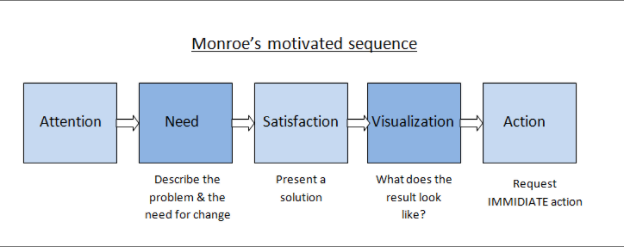

The sequence is made up of five steps. Generally speaking, each step should be delivered in order. And each contains a vital ingredient in the recipe we’re trying to cook.

Step 1: engage the audience’s attention. Audiences are made up of humans. Humans have short attention spans. They’re looking for something interesting, so oblige them with a joke, a relevant anecdote, a thesis statement, praise, or something else that sets the scene.

Step 2: establish need. Present the problem that needs addressing and describe the need for change. The current government is driving the country into the toilet. Not enough kids are graduating school with the right reading level. People can’t transfer money across borders as conveniently as they could.

Step 3: satisfy the need. Propose your solution. Vote those bums out (and replace them with me!). A new way to get young kids reading. A technological solution that enables the simple, instantaneous transfer of money.

Step 4: visualisation. What does the good outcome, which are you trying to attain, look like? This is where you can add detail and, crucially, maximise the emotional impact of the speech. The country will be happier, wealthier and wiser under a government led by me. A generation of kids will grow up with a love of reading. People will be able to send their hard-earned money to their families back home.

Step 5: call to action. Now that the audience is putty in your hands, don’t waste the attention you have created. Request that they do something which is connected with the message you are trying to promote. Get the audience to vote (for you). To publicise your campaign. To invest in your new app. Send them home with your message ringing in their ears.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

What is the lesson?

Once you learn about Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, don’t be surprised if you detect its fingerprints on every bit of persuasive rhetoric you encounter. This is partly a result of the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon. But it’s also because, whether you know its formal name or not, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence gives logical structure to something which we all know deep down.

This thing that we know deep down is actually the hidden truth of being a speechwriter. I promise I’m only exaggerating a tiny bit when I say this is the reason that there is a market for the work we do. Here is the hidden truth: stories matter more than facts.

In a world where only facts mattered, there’d be no speechwriters. A speaker could simply note all the salient facts about their subject, present them to the audience, and then depart the stage, confident that she had achieved her purpose.

Stories, narrative and emotions are what win the day. With very few exceptions, such as if you are addressing a highly analytical audience, persuasive speeches are stories, except one where you’re asked to implement the moral at the end.

I’m reminded of an illustrative example I encountered when attending an online speechwriting course several years ago. Investigators at the Wharton School of Economics went around campus and offered students a small payment if they agreed to a small survey about their use of personal technology. Unbeknownst to the students, investigators were actually testing what the students would do with the money they received. Envelopes were placed nearby, with two different appeals for donations.

The first appeal was personal and emotive: “any money that you donate will go to Rokia, a 7-year-old girl from Mali. Rokia is desperately poor and faces the threat of severe hunger or even starvation.”

The second appeal was dry and factual: “food shortages in Mali affect 3m children. In Zambia, severe rainfall deficits have resulted in a 42% decline in maize production. Four million Angolans have been forced to flee their homes.”

In a finding that should surprise no one, the first appeal elicited twice as many donations. In fact, the second appeal deterred people from giving at all. Its framing made the situation seem hopeless, and completely unsolvable by any individual.

The main insight of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is that its steps – establishing the need, satisfying the need, visualising the solution and calling for action – are the keys to persuading your audience.

But we should also be careful about not over-learning its lesson. Monroe’s sequence is about the structure of a speech (or, for professionals in advertising, an ad) – its outline. Following Monroe enables you to write a persuasive speech. But to actually persuade, you still need to engage your audience with humour, flair, astonishing statistics, charismatic delivery (ideally, all of the above!).

Structure isn’t everything. A building with an impressive frame but no walls, floors or lifts isn’t fit for purpose. It’s not even really a building.

Conclusion

Most of my clients, regardless of their industry, are ultimately in the persuasion business. So Monroe’s Motivated Sequence informs, at least subtly, most of the speeches I write. But there are other kinds of speeches and, accordingly, other speechwriting techniques. I’ll explore some of those in future blog posts (consider this an unofficial first entry in a series).

For the simple reason that not every speech is meant to persuade, Monroe’s Motivated Sequence won’t solve every problem. It’s one tool, among many, in the speechwriter’s toolbox. If I were to compare it to any tool in particular, I’d say it’s like the hammer. It’s strong. Despite how tempting it might be, it can’t be used for everything. But, in the right hands, it is incredibly important. And it might be the tool you find yourself reaching for most often.